By Patricia Young

It’s hard to believe now but not too long ago, smoking on airplanes was the norm. Taking a flight meant hours of breathing toxic tobacco smoke-filled air. Being a flight attendant (back then we were called stewardesses) meant spending entire days with tobacco smoke in our faces. Today, no one would dream of lighting up on a plane but when I first started flying, the thought of doing something about it seemed impossible…for everyone but me.

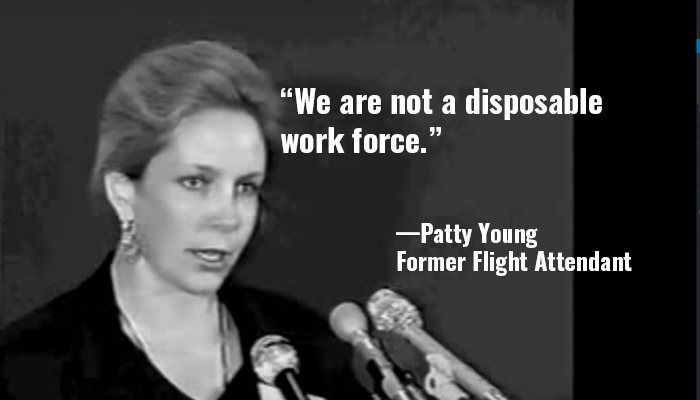

Sick of being held hostage at 35,000 feet, my fellow flight attendants and I took on the most diabolical, powerful industries to win the right to breathe clean air at work. It felt like an impossible fight. The tobacco lobby was larger than ever, airline executives dismissed our concerns, and many passengers couldn’t conceive of flying without their cigarettes. But despite the odds, we persisted. We had to—our sanity and health depended on it.

When I started flying in the summer of 1966, my colleagues warned me: while the job had beautiful perks—traveling the world and meeting fascinating, interesting people—it also required inhaling toxic cigarette smoke. They said that despite never picking up a cigarette, they had the lungs of smokers. Our annual company medical exams confirmed this. When I asked medical professionals why healthy non-smokers were suffering from smoking-related diseases, no one could answer. The medical community hadn’t yet acknowledged what we know all too well today: secondhand tobacco smoke maims, causes disabilities, and often leads to an early death sentence.

Our fight was an uphill battle. Throughout it, we were dismissed, harassed, and threatened. We pleaded with airline executives and testified before Congress. We took our case to the press and the public, carrying signs that said “Secondhand Smoke is Pulmonary Rape!” We joined clinical studies to prove the dangers of secondhand tobacco smoke and filed lawsuits — including a class action.

Finally in 1988, smoking was banned on domestic flights of less than two hours. But some airlines would game the system—adding extra flying time and counting short flights to Mexico and Canada as domestic instead of international. In February 1990, this ban was extended to domestic flights of less than six hours. By 2000, smoking was banned on all domestic and international flights entering or leaving the country. It was the beginning of the end to a horrible chapter in our nation’s public health history, sparking a movement to eliminate secondhand tobacco smoke from workplaces across all industries. Since then, smoking has vanished from a lot of public places, and most Americans are protected from secondhand tobacco smoke in their daily lives. But 35 years later, some working people are still subjected to the harms of secondhand tobacco smoke.

While many states are smoke-free across bars, restaurants, and other work places, there are still loopholes. For example, approximately 14 states (including Nevada, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) allow smoking in casinos, forcing card dealers, custodians, security guards and other workers in states to go to work in toxic smoke-filled rooms every day, forced to choose between their life and a paycheck.

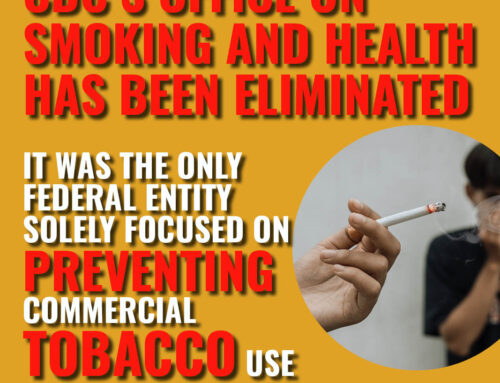

During the COVID-19 pandemic, New Jersey temporarily eliminated smoking in casinos to protect public health. Ironically, this pandemic measure marked the first time workers could breathe easy and safely. When this policy was lifted, casino workers saw their health threatened once more. In response, Casino Employees Against Smoking Effects (CEASE) was formed, first as dozens and now as more than 3,000 members mobilizing workers, gathering support from lawmakers, and fighting in the courts. While their work is far from finished, casino workers have fought tirelessly for many years to call attention to their cause, and it is up to us to support them.

When we fought to make airlines smokefree, the industry warned of dire economic consequences. Instead, air travel flourished. The same fear tactics were used in restaurants, bars, and offices, and yet, those workplaces quickly adapted and thrived. And while many people think gambling and smoking go hand in hand, public opinion is changing fast: smoking is at a historic low, and according to the Surgeon General’s 2024 report, the vast majority of people want smoke-free casinos. The truth is, people want clean air, businesses do just fine without smoking, and smoke-free policies save lives.

I once said that “flight attendants are the canaries in the coal mines and are the major power in the world who forced the no smoking issue into a global movement!” Casino workers are today’s canaries. And just like us, they’re being ignored AND ABUSED. But here’s the thing — they’re going to win. The question is how long it will take and how many will suffer illness and death in the process. To the casino workers fighting for their rights: do not give up. Your health and lives matter, and despite all the pushback, the truth is on your side.

State lawmakers need to stop pandering to the tobacco industry leaders and close their casino smoking loopholes. Casino executives MUST grow a spine and enact 100% smoke-free indoor policies, and new casinos must open as smoke-free facilities. In the meantime, we must support these workers and demand action — possibly, like I did, by acting boldly and picketing casinos with large provocative signs to help save our lives. After all, we non-smokers who are being threatened and murdered by second-hand smoke have value: we love, we have wonderful lives with families, we want to live! We do our best to work in public places but we are put in dangerous tobacco smoke. We are being willingly murdered by the tobacco companies and the people who help them as they sell cigarette smoke all over our world!

The movement I started 59 years ago is not over until every person in a workplace, public place, and home is protected from secondhand tobacco smoke. Tobacco smoke kills 8+ million people per year globally. While the tobacco industry makes huge profits wherever tobacco products are sold, they cause disease, suffering, disabilities, and early death.