African Americans and Coronavirus: Health Disparities and the Role of Social and Political Determinants of Health

The news that African Americans are falling at a disproportionate rate from COVID-19 is alarming, but not surprising. Public health advocates have long been sounding the alarm that African Americans, and black and brown communities as a whole, are the most vulnerable to death and disease due to social and political determinants of health. While many will point to underlying conditions as the sole source of the disparities, we must also consider how these conditions came to be.

Being healthy is more than the outcome of a state of mind or lifestyle choices. “Healthy” is a way of life that is often out of reach for millions of Americans, particularly African Americans, who are encumbered by a long history of systemic racism and exclusion from the things that allow people to maintain good health, including accessible and affordable quality foods, livable wages, health insurance, community health centers, avoiding misdiagnoses, affordable prescriptions and treatment when properly diagnosed, transportation (to work, a doctor’s office, pharmacy, grocery store), and quality education (to compete for jobs that pay at or above livable wages and provide health insurance). Good health is the byproduct of health equity, and health equity has been dangled out of the reach of the black community for centuries.

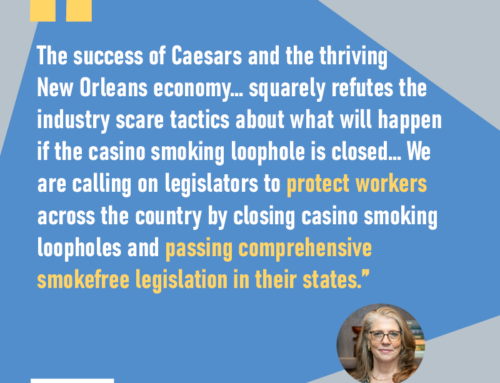

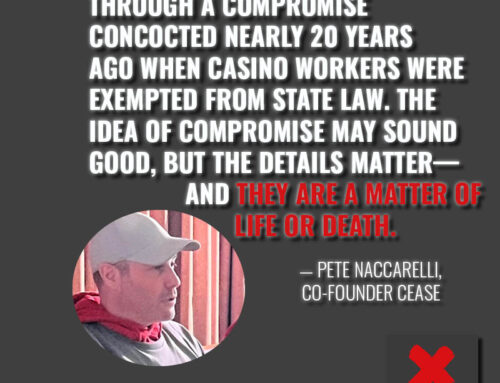

It is widely known that African Americans suffer disproportionately from chronic illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and respiratory illness including asthma and COPD. A cross-section of risk factors points to tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure as major contributors. According to the CDC, African American children and adults are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke in the home or workplace than any other racial or ethnic group. No matter where people live, work, or play, they all have a right to breathe air that is free from tobacco smoke, which contains toxins that damage the heart, lungs, mouth, and more. In its report Bridging the Gap: The Status of Smokefree Air in the United States, the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation notes that a just society ensures that everyone — regardless of age, race, income, or occupation from health risks in their environments — is protected by making smokefree policy a part of every health equity effort.

For far too long, the issue of health disparities has been a “us vs. them” problem. Outside of public health, many have asked the question, “Why should I care?” Make no mistake, this is an us problem. If comorbidities make our fellow citizens more susceptible to this deadly illness, especially one that shows to be casually transmissible, it is in our best interest to remove the barriers to good health and aggressively pursue health equity. As a nation, we can no longer watch black and brown communities get crippled by growing health disparities and wash our hands of the responsibility to make a course correction. This pandemic is proof that we are the sum of our parts and a healthy America benefits us all.

Onjewel Smith is the Southern States Strategist for the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. She has worked in the nonprofit sector for more than 25 years helping organizations and communities build capacity for sustainable change. Throughout her career, she has provided technical assistance in the areas of community organizing, grassroots advocacy, and social justice issues.