Many states have now legalized marijuana/cannabis not only for medical use, but also for recreational use (39 plus DC). To state the obvious, there are key differences between decriminalization and/or providing safe medical access vs the realities of multi-billion dollar mass commercialization increasingly backed by tobacco companies, retailer networks, and their allies.

A commercial industry for marijuana consumption has been created in the U.S., and it has one overriding goal: to normalize marijuana use, including smoking and vaping, everywhere and to have it regulated “just like alcohol.” Lawmakers often view marijuana regulation through a lens of revenue growth vs health. Tobacco and marijuana retailers frame expansion as ways to fight black market sales, support small businesses, and to grow revenue.

Following the early wave of independent marijuana dispensaries, there is a glut of supply and collapsing prices in states like California, making it harder for these venues to compete against unlicensed sellers and cheap mass market retailers like convenience stores.

Big Tobacco in the Mix

Tobacco giants Altria and Reynolds American together with convenience store retailer networks have invested billions into the marijuana industry and actively support legalization. They have been trying to position themselves as legitimate stakeholders for developing the policies that will regulate their marijuana products and profits. The Coalition for Cannabis Policy, Education, and Regulation (CPEAR) is the tobacco industry’s effort to support marijuana legalization and to target lawmakers.

As the trend toward normalizing public smoking of marijuana grows, we need to be aware that more laws will be proposed to weaken smokefree protections at the state and local level to allow for broader use of smoking marijuana in public places and workplaces. Today’s marijuana industry is starting to look and act more like the tobacco industry – a commercial enterprise seeking to maximize sales, profits, and product consumption, and backed by marketing campaigns, lobbyists, and lawyers to shape regulation. At the same time, tobacco is starting to look a little more like marijuana – seeking to dovetail on any opportunity to renormalize smoking in social environments, like bars, and pushing to allow for indoor use of e-cigarettes and “vape pens” that can be used to consume both tobacco and marijuana products.

As the marijuana/cannabis industry grows and is legalized, public health professionals are adapting to what this entails for their smokefree laws and policies, such as an increase in marijuana smoking and exposure to secondhand marijuana smoke. Regardless of the debate of possible benefits of marijuana products, there is simply no need to use them inside shared air spaces (such as workplaces, public places, colleges, and multi-unit housing) where others are then subject to the hazardous secondhand smoke. Just like traditional cigarettes, marijuana should be used in ways that don’t impact the health of others.

Be Prepared!

Nobody should have to breathe secondhand marijuana smoke at work or where they live, learn, shop, or play. Smoke is smoke, and marijuana smoke is a form of indoor air pollution.

Therefore, it is important to strengthen all smokefree laws – both existing and new – to include marijuana in the definitions of smoking and vaping. Since 2010, ANR’s model smokefree ordinances and policies have included marijuana as a product prohibited in smokefree environments. By including marijuana smoke, it effectively eliminates any potential confusion by clearly defining smoking as “inhaling, exhaling, burning, or carrying any lighted or heated cigar, cigarette, pipe, hookah, or any other lighted or heated tobacco or plant product intended for inhalation, whether natural or synthetic, including marijuana/cannabis, in any manner or in any form.” The definition also includes the vaping of any substance.

For more information, refer to ANR’s Secondhand Marijuana Smoke fact sheet

Secondhand Marijuana Smoke Contains Hundreds of Chemicals

– Just Like Secondhand Tobacco Smoke

Peer-reviewed and published studies indicate that exposure to secondhand marijuana smoke can have health and safety risks for the general public, especially due to its similar composition to secondhand tobacco smoke.

If marijuana smoking is allowed indoors in public places and multi-unit housing, employees, patrons, and residents are at risk. Secondhand smoke exposure from marijuana can cause significant health issues, including breathing problems.

- Secondhand smoke from combusted marijuana contains fine particulate matter that can be breathed deeply into the lungs,1 which can cause lung irritation, asthma attacks, and makes respiratory infections more likely. Exposure to fine particulate matter can exacerbate health problems especially for people with respiratory conditions like asthma, bronchitis, or COPD.2

- Significant amounts of mercury, cadmium, nickel, lead, and chromium are found in marijuana smoke, and there is three times the amount of ammonia and more hydrogen cyanide in marijuana smoke than there is in tobacco smoke.3

- In 2009, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment added marijuana smoke to the list of carcinogens and reproductive toxins cited as dangerous in the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, also known as Proposition 65. It reported that at least 33 individual constituents present in both marijuana smoke and tobacco smoke are Proposition 65 carcinogens.4, 5

- Secondhand smoke from marijuana has many of the same chemicals as smoke from tobacco, including those linked to lung cancer.6

- Secondhand marijuana smoke exposure impairs blood vessel function. Thirty minutes of exposure to secondhand marijuana smoke at levels comparable to those found in restaurants that allow cigarette smoking led to substantial impairment of blood vessel function. Marijuana smoke exposure had a greater and longer-lasting effect on blood vessel function than exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke.7

- Secondhand marijuana smoke and secondhand tobacco smoke likely have similar harmful health effects, such as atherosclerosis (partially blocked arteries), heart attack, and stroke, because of their similar chemical composition.

- Particulate levels from secondhand marijuana smoke are even higher than particulate levels from secondhand tobacco smoke. A study comparing indoor particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) levels from secondhand marijuana smoke and secondhand tobacco smoke concluded that “the average PM2.5 emission rate of the pre-rolled marijuana joints was found to be 3.5 times the average emission rate of Marlboro tobacco cigarettes, the most popular US cigarette brand.” Smoking a marijuana joint indoors can produce extremely high indoor PM2.5 concentrations, thereby exposing the public and workers to dangerous secondhand marijuana smoke emissions.8

- Being near people who are using inhaled marijuana is hazardous to human health. In a dispensary that allowed marijuana/cannabis smoking, research scientists discovered that the average PM2.5 emissions was 840 ug/m3 over 9 visits, which exposed patrons and workers to air pollutant concentrations that are beyond hazardous levels.9

To learn more, refer to ANR’s Secondhand Marijuana Smoke fact sheet available at https://no-smoke.org/secondhand-marijuana-smoke-fact-sheet.

Issues and Policy Trends

As the marijuana industry ramps up to become as influential and aggressive as Big Tobacco, there is an urgency for public health professionals and advocates to get ahead of policy trends for marijuana use in states and communities.

Here are some tips for what to expect from marijuana industry proponents and how to prepare to protect nonsmokers’ rights:

1. Marijuana and electronic smoking devices

If a state legalizes marijuana use, state and local smokefree laws should define smoking to include the smoking of marijuana as well as the use of electronic smoking devices. If a smokefree law does not prohibit the use of electronic smoking devices in smokefree spaces, this means that marijuana vaping is, by default, allowed in workplaces, bars, restaurants, and other public venues unless prohibited by an individual business policy. Thus, if not specifically prohibited, everyone else in the building has to breathe the smoke. Nonsmokers should not have to breathe other people’s secondhand marijuana smoke or vaped aerosol in smokefree spaces like workplaces, public places, and apartment buildings.

Contact ANR for sample policy language.

2. Smoking lounges and semi-enclosed areas

A challenge for marijuana regulation is to identify appropriate places for use of the product. Expect a lot of pressure to enable marijuana use in enclosed areas (smoking “lounges” or “clubs” especially attached to retailers) and semi-enclosed areas (rooftop bars and patios). Some proposed laws would allow food and drink sales at marijuana retailers, turning them into hospitality venues that allow smoking indoors. The question to ask is: how will allowing marijuana smoking affect other people? Do people work or volunteer there? Will non-users be exposed to secondhand marijuana smoke or thirdhand smoke residue? Will marijuana smoke drift into neighboring businesses or property?

People should not have to breathe smoke of any kind while at work or when in public places.

3. New definitions and terms

Expect marijuana industry proponents to come forward with new loosely defined terms not addressed by current smokefree laws. The industry will also try to redefine old terms like “hospitality” or “public” in ways more favorable to their purposes of normalizing marijuana use everywhere. Be sure to refer back to ANR’s model language for clearly defined terms and restrictions.

4. Watch the money

The huge amount of money to be made by this new industry is hard for policy makers, states, communities, and organizations to resist. Yet this money comes with strings attached. Be sure to keep an eye open to this new industry masquerading as partners and “benefactors,” all the while expecting policies to be passed to benefit smoking everywhere while ignoring the health of workers and the public. Tobacco industry companies including Altria and Reynolds America and retailers including convenience stores are also active in the marijuana industry. Review the groups and partners of Altria’s marijuana/ cannabis lobbying group that targets lawmakers and seeks to influence legislation.

5. Cannabis learning from casinos

Legalizing marijuana is often promoted as an economic growth opportunity, and states and communities focus on these perceived “green wave” revenue opportunities, sometimes to the detriment of other considerations such as public health concerns. Parallels can be seen between cannabis legalization and the similarly rapid expansion of the casino gaming industry, where the industry has promised local revenue boosts that may not be realized. The mass commercialization of cannabis and the expansion of retail stores are saturating the market in some areas, and perhaps the novelty of access has worn off a bit. In many states, including Illinois, the gaming industry evolved from only a handful of casino licenses to having slot machines located in numerous types of businesses, all in the name of growing tax revenue, combating unlicensed (‘black market’) machines, and supporting small businesses.

Additionally, one of the reasons why smokefree air protections are at risk from cannabis expansion is the growing industry argument that legal cannabis retailers are suffering economically and need relief to fight against a black market. In California, AB374 in the 2023 legislature would allow marijuana retailers to sell food, non-alcoholic beverages, and hold concerts – which would open the door to restaurants and other venues that allow indoor smoking and vaping – and the bill sponsor is promoting the legislation as a way to “help pot shops struggling to compete with the illegal market to attract new customers.”

Ventilation Cannot Protect You From the Harmful Effects of Secondhand Smoke.

Period.

The old tobacco industry tactic of proposing ventilation systems to solve the secondhand smoke problem is being dusted off and promoted by the marijuana industry. Industry lobbyists and proponents say, “Just put a ventilation system into your marijuana club, and the secondhand smoke problem is solved.” Nothing could be further from the truth.

As has been proven time and time again, ventilation does not eliminate all the poisonous toxins and chemical components of secondhand smoke. The science is clear. Ventilation systems or air cleaning technologies may reduce odor, but they do not address the serious health risks caused by secondhand smoke exposure. Research is showing that negative health impacts, especially to the cardiovascular system, occur quickly even at extremely low levels of exposure to secondhand marijuana smoke. The only way to eliminate the health hazards of secondhand smoke is by having a 100% smokefree environment.

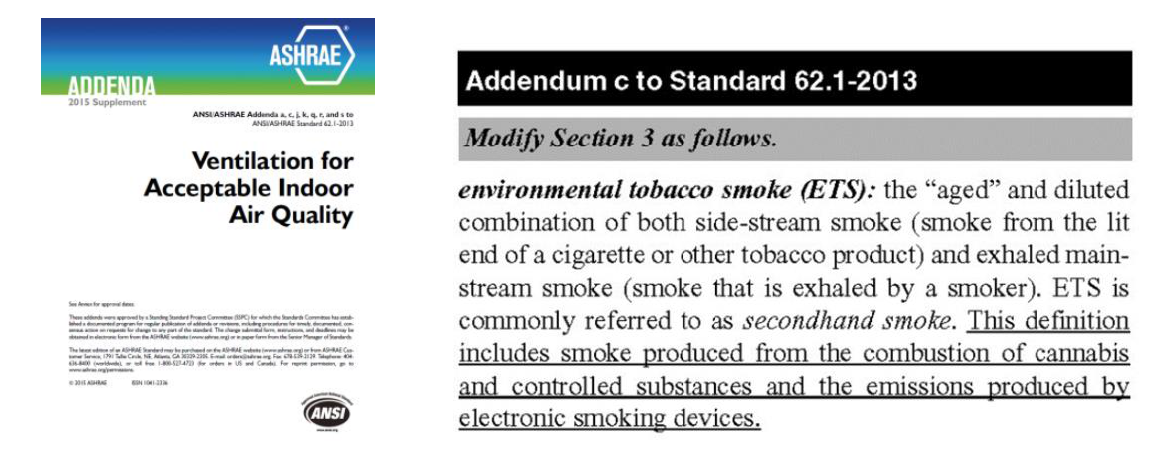

The Board of Directors for the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), the international standard-setting body for indoor air quality, unanimously adopted an important position statement on secondhand tobacco smoke at its summer 2005 conference.

ASHRAE Standard 62.1 reaffirms:

- There is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke.

- Ventilation and other air filtration technologies cannot eliminate all the health risks caused by secondhand smoke exposure.

- Tobacco smoke does not belong in indoor areas.

In 2013, the Standard was amended to state:

- Marijuana smoke should not be allowed indoors.

- Emissions from electronic smoking devices should not be allowed indoors.

The “ASHRAE Position Document on Environmental Tobacco Smoke” was again approved.

According to this position statement, “ASHRAE holds the position that the only means of avoiding health effects and eliminating indoor ETS exposure is to ban all smoking activity inside and near buildings.”

The fact remains that the only way to eliminate the health hazards of secondhand smoke—from tobacco or marijuana smoke or emissions from electronic smoking devices—is with a 100% smokefree environment.

Opposition Arguments and Activities

Remember: The marijuana industry’s goal is to make marijuana use (including smoking) as “normal” as alcohol use. To achieve this goal, the industry will continue to support legislation for regulating marijuana just like alcohol and not like tobacco.

CASE STUDY: DENVER

Colorado voters legalized recreational marijuana in 2012. In Denver, the marijuana industry narrowly won a ballot initiative (Measure 300) in November 2016 to allow marijuana use, including smoking or vaping, in “approved neighborhoods” throughout the city. Even though several Denver businesses allowed marijuana smoke indoors, their success was questionable. Regardless of the outcomes of Measure 300, Denver City Council eventually opted into legislation (see Colorado below) to exempt marijuana smoke from the Colorado Clean Indoor Air Act.

CASE STUDY: COLORADO

In mid-2019, Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed the “Marijuana Hospitality Establishments” law, which allows for smoking marijuana in businesses and food service establishments if certain criteria are met. As a result of this pro-marijuana business law, Colorado became the first state to lose its statewide smokefree restaurant status on ANR Foundation’s lists and maps. Research on lobbying from the new cannabis industry found that the industry dedicated significant resources towards lobbying the Colorado State Legislature on behalf of policies intended to increase cannabis use. An astounding $7 million (inflation adjusted) was spent by the cannabis industry from FY 2010-2021 to lobby the Colorado legislature on 367 bills. Over $800,000 (11% of total cannabis spending) was from out-of-state clients. In 48% of lobbyist reports, lobbyists did not disclose their funder’s cannabis affiliation, and cannabis organizations used strategies that may have obscured the true amount and source of funding. Lobbyists and agencies concurrently represented the alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis industries, possibly facilitating inter-industry alliances when interests align.

Some local jurisdictions in Colorado have taken a stand for community health by not opting into the pro-marijuana use law and thereby keeping secondhand marijuana smoke out of local restaurants and marijuana hospitality establishments within their communities.

In Boulder, Cannabis Licensing Advisory Board (CLAB) member Robin Noble said, “The downsides of licensing marijuana-consumption businesses outweigh potential benefits.” Ms. Noble continues, “My opposition [to allowing marijuana smoking in hospitality establishments] is informed by stakeholders who presented to CLAB, including the Boulder city staff, who oppose it citing the risks of secondhand smoke exposure to workers and first responders.”

CASE STUDY: ALASKA

Alaska voters legalized recreational marijuana in 2014, and their Marijuana Control Board sets the regulatory process for marijuana growth, sales, and consumption for the state. During each of the five public comment periods for their regulatory process, the general public has submitted an abundance of comments against allowing marijuana smoking in public. However, regardless of proper procedure and overwhelming public comment against marijuana smoking and secondhand exposure, the Marijuana Control Board moved forward with regulations to allow smoking in approved public places. When citizens in Alaska voted to legalize recreational marijuana use, they were assured by bill language that marijuana would not be smoked or vaped openly and publicly. It is an industry tactic to then push legislation and regulations for redefining “public” spaces as indoors away from public view in “private” venues such bars, yoga studios, coffee shops, on-site use clubs, etc. This is contrary to the will of the general public and opens up more places for indoor smoking. Local Tobacco Prevention and Control advocates are energized and motivated to keep a close eye on the regulatory process as it pertains to keeping their local smokefree laws strong and free from secondhand marijuana smoke indoors.

CASE STUDY: CALIFORNIA

California’s adult-use marijuana law was adopted in 2016, and it prohibits marijuana smoking and vaping wherever tobacco smoking and vaping is prohibited. This means most indoor workplaces and public places, including all restaurants and bars, are free from all types of secondhand smoke. Smoking and vaping is still permitted in tobacco retailers and their attached lounges. California’s marijuana law allows local jurisdictions to decide whether to permit marijuana retailers, and if so, if they will allow onsite use at the retailer, in line with what is permitted at tobacco retailers. Some jurisdictions have decided to allow smoking and vaping inside marijuana retailers, while others have decided not to allow it.

As expected, marijuana industry proponents have worked both locally and at the state level to expand where people can smoke and vape marijuana. These proposals aim to create social consumption spaces that would roll back smokefree workplace protections and expose hospitality workers to secondhand smoke on the job. The City of West Hollywood adopted an ordinance to allow marijuana consumption cafes and lounges where diners could smoke and vape marijuana while having a meal, and the first cafe opened in 2019. The state legislator who represents West Hollywood then introduced a bill to legalize marijuana consumption cafes statewide, which did not pass.

In 2023, a similar but more expansive state bill was introduced that would allow marijuana retailers to serve food and nonalcoholic beverages, as well as sell tickets to events like concerts, which would create a variety of marijuana cafes and hospitality venues that allow indoor smoking and vaping. If the bill is passed, it would eliminate smokefree workplace protections that California has provided to hospitality workers and patrons since 1998. After 25 years of smokefree air on the job, food service and other hospitality workers are now at risk of becoming a new class of worker who are required to be exposed to increased indoor air pollution from secondhand smoke in order to do their job.

ANR’s position is that marijuana smoking should be prohibited in these venues. Regardless of what is being smoked, it should not be smoked in ways that negatively impact other people’s health and well-being. Smoke is smoke. Secondhand marijuana smoke, like tobacco smoke, contains thousands of chemicals, many of which are toxic. The smoke also contains hazardous fine particles (PM2.5) that pose a significant respiratory health risk to nonsmokers. Similarly, the secondhand aerosol emitted from electronic smoking devices also contains ultrafine particles, toxins, carcinogens, volatile organic compounds, and nicotine, and thus poses a public health risk.

We believe that laws and policies should make it clear that marijuana smoking and vaping should not be allowed in workplaces and public places, both indoors and outdoors.

Tobacco & Marijuana Smokefree Policy Trends

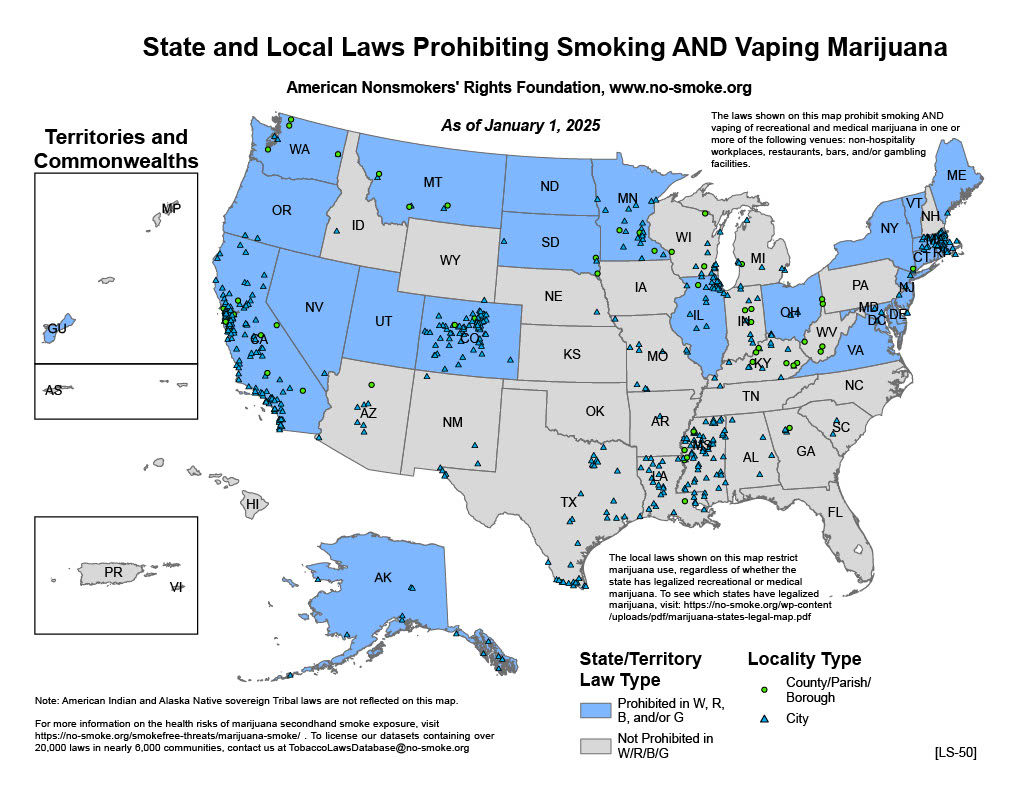

Laws addressing marijuana have grown from approximately 30 local laws in January 2014 to 1068 local laws in January 2025. These numbers are the sum total of all laws/policies in the U.S. Tobacco Control Laws Database© that address or mention marijuana.

As of January 1, 2025, 1068 localities and 40 states/territories/commonwealths restrict marijuana use in some or all smokefree spaces. Of these, 585 localities and 22 states/ territories/commonwealths prohibit smoking and vaping of recreational and medical marijuana in one or more of the following venues: non-hospitality workplaces, restaurants, bars, and/or gambling facilities.

Resources and Recommendations

Legalization and commercialization of marijuana is posing significant challenges for public health in general. Marijuana, legal or not, still creates secondhand smoke, which is a form of indoor air pollution. If we truly want safe, healthy, smokefree spaces, then they should be free from particulate matter created by tobacco cigarette smoke, marijuana smoke, and secondhand aerosol from electronic smoking devices.

Therefore, ANR’s model policies and ordinances have included marijuana as one of the products that cannot be used in a smokefree environment since 2010:

“Smoking” means inhaling, exhaling, burning, or carrying any lighted or heated cigar, cigarette, pipe, hookah or any other lighted or heated tobacco or plant product intended for inhalation, whether natural or synthetic, including marijuana/cannabis, in any manner or in any form. “Smoking” also includes the use of an electronic smoking device which creates an aerosol or vapor, in any manner or in any form, or the use of any oral smoking device for the purpose of circumventing the prohibition of smoking in this Article.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Refer to ANR’s Model 100% Smokefree Ordinance for language on including marijuana in smokefree policies.

- Review ANR Foundation’s On-Site Cannabis Consumption Policy Guidance Tipsheet.

- Track and expose opposition activities.

- If you haven’t already done so, add electronic smoking devices to your smokefree laws.

- Be prepared for proposed roll-backs of smokefree protections and redefining “public.”

- Stick to the secondhand smoke health message, even when referring to use of medical marijuana. Regardless of how one feels about marijuana use, no one should have to breathe secondhand marijuana smoke at work, in public, or where they live.

To assist the tobacco control movement with facts and resources about secondhand marijuana smoke, we have created a few fact sheets and infographics. Visit no.smoke.org/marijuana for these resources. Our subject matter experts are also available to speak to groups and coalitions about preparing for and responding to marijuana secondhand smoke issues and policies. Contact us at 510-841-3032 or info@no-smoke.org.

May be reprinted with appropriate attribution to American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation.

Copyright 2025 American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. All rights reserved.

REFERENCES

- Hillier, FC., et al. “Concentration and particle size distribution in smoke from marijuana cigarettes with different Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol content.” Fundamental and Applied Toxicology. Volume 4, Issue 3, Part 1, June 1984, Pages 451-454. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0272059084902021

- “Air and Health: Particulate Matter.” National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network, U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. http://ephtracking.cdc.gov/showAirHealth.action#ParticulateMatter

- Moir, D., et al., A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem Res Toxicol 21: 494-502. (2008).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18062674 - “Evidence on the Carcinogenicity of Marijuana Smoke.” Reproductive and Cancer Hazard Assessment Branch, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California Environmental Protection Agency. August 2009. http://oehha.ca.gov/prop65/hazard_ident/pdf_zip/FinalMJsmokeHID.pdf

- Wang, X., et al., “Brief exposure to marijuana secondhand smoke impairs vascular endothelial function” (conference abstract). Circulation 2014; 130: A19538. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/130/Suppl_2/A19538.abstract

- “Evidence on the Carcinogenicity of Marijuana Smoke.” Reproductive and Cancer Hazard Assessment Branch, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California Environmental Protection Agency. August 2009. http://oehha.ca.gov/prop65/hazard_ident/pdf_zip/FinalMJsmokeHID.pdf

- Wang, X., et al., “Brief exposure to marijuana secondhand smoke impairs vascular endothelial function” (conference abstract). Circulation 2014; 130: A19538. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/130/Suppl_2/A19538.abstract

- Ott, W. et al. “Measuring indoor fine particle concentrations, emission rates, and decay rates from cannabis use in a residence.” Atmospheric Environment: X, Volume 10, 2021, 100106, ISSN 2590-1621, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeaoa.2021.100106. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S259016212100006X)

- Huang, Murphy, Jacob and Schick. “PM2.5 Concentrations in the Smoking Lounge of a Cannabis Store.” Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 6, 551–556, Publication Date: May 26, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00148, Copyright © 2022 American Chemical Society