The 2006 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report, “The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Secondhand Smoke,” concluded that 100% smokefree workplace policies are the only effective way to eliminate secondhand smoke exposure in the workplace. Even sophisticated ventilation systems do not eliminate the health hazards of secondhand smoke.1 Casino, bar, and restaurant workers remain significantly more exposed to toxic secondhand smoke in their jobsite compared to other segments of the U.S. workforce.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends making all casinos 100% smokefree to ensure indoor air within casinos is safe for workers to breathe.

SECONDHAND SMOKE CAUSES DEATH AND DISEASE IN CASINO WORKERS AND PATRONS

- A federal report from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) found that casino workers are exposed to hazardous levels of toxic secondhand smoke at work, including tobacco-specific carcinogens that increased in the body as the shift went on.2

- Casino workers are at greater risk for lung and heart disease because of secondhand smoke exposure.3

- Six out of every 10,000 nonsmoking Pennsylvania casino workers will die each year because of exposure to secondhand smoke.4

- Casino workers even in a “well-ventilated” casino have cotinine (metabolized nicotine) levels 300-600% higher than in other smoking workplaces during a work shift.5

- The average level of cotinine (metabolized nicotine) among nonsmokers increased by 456% and the average levels of the carcinogen NNAL increased by 112% after four hours of exposure to secondhand smoke in a smoke-filled casino with a “sophisticated” ventilation system.6

- Smoke-filled casinos have up to 50 times more cancer-causing particles in the air than highways and city streets clogged with diesel trucks in rush hour traffic. After going smokefree, indoor air pollution virtually disappears in the same environments.7

- Casino employees occupationally exposed to secondhand smoke suffer from increased risk of DNA-damage, which then leads to even greater risk of developing cancers and heart disease.8

- A survey of 559 London casino employees found that 95% of polled workers reported the presence of sensory irritation symptoms (i.e., runny nose, sneezing, or nose irritation, red eyes) and 84% with respiratory symptoms (i.e., cough, shortness of breath, bring up of phlegm). These measurements are significantly higher than that reported in similar studies of bar workers.9

- After the implementation of Ontario, Canada’s Smokefree Indoor Air Law, levels of the carcinogen NNAL were reduced by 52% in nonsmoking casino employees and cotinine (metabolized nicotine) levels fell by 98%.10

VENTILATION CANNOT CONTROL FOR HEALTH: PERIOD.

Ventilation and air filtration systems do not protect workers or patrons from exposure to secondhand smoke. These systems can reduce odor, but not the health hazards. The U.S. Surgeon General determined that there is no “risk-free level of exposure to secondhand smoke.” Separating smokers from nonsmokers, installing smoking rooms, or even sophisticated air cleaning technologies cannot eliminate the health hazards of secondhand smoke exposure nor remove all the poisons, toxins, gases, and particles found in secondhand smoke. Additionally, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems can distribute secondhand smoke throughout a building.11

- The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) position document states: “At present, the only means of effectively eliminating health risks associated with indoor exposure is to ban smoking activity… No other engineering approaches, including current and advanced dilution ventilation or air cleaning technologies, have demonstrated or should be relied upon to control health risks from ETS [environmental tobacco smoke] exposure in spaces where smoking occurs… Because of ASHRAE’s mission to act for the benefit of the public, it encourages elimination of smoking in the indoor environment as the optimal way to minimize ETS exposure.”12 Additionally, ASHRAE does not specify ventilation rates or procedures for smoke-filled hospitality venues.”

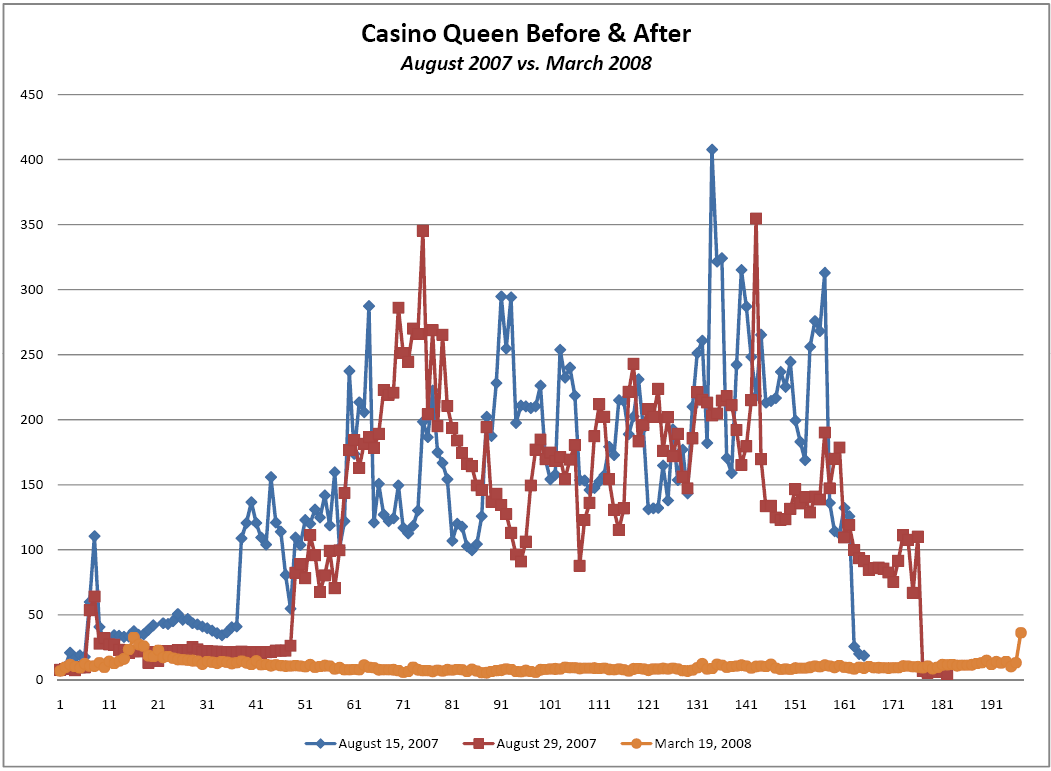

- In Illinois casinos, air pollution levels went from being over 400 PMs in gaming areas (considered “hazardous” by the U.S. EPA’s air quality index) down to 15 PMs and “healthy” after the statewide smokefree indoor air law went into effect. When researchers measured the hazardous air, they noted that less than seven percent of gaming patrons were smoking.” (See chart below)13

- A study by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, found that air quality in casinos improved 92% after the casinos became smokefree under the Colorado Clean Indoor Air Act on January 1, 2008. Before the law, casino employees and patrons were exposed to an “unhealthy” level of air pollution according to EPA ratings. Some establishments showed indoor air pollutant levels to be twice as harmful as the worst forest fire air quality measurements ever detected in Denver by the Regional Air Quality Council. After the smokefree law took effect, casinos now have an EPA rating of “good,” along with the state’s restaurants and bars.14

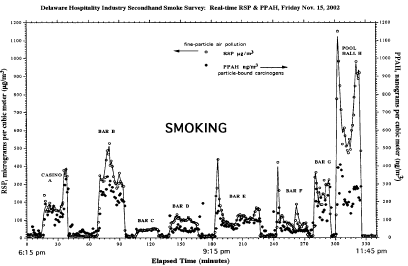

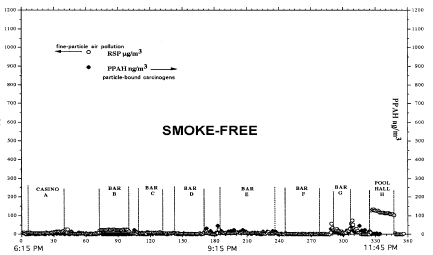

- Even sophisticated ventilation technology in a Wilmington, Delaware casino did not protect workers and patrons from secondhand smoke exposure. After the state’s smokefree law took effect, however, the levels of the carcinogen PPAH and other air pollutants caused by secondhand smoke decreased dramatically. (See chart below)15

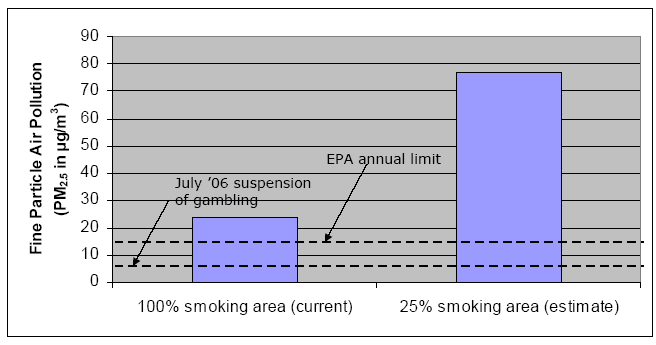

- Indoor air quality measured in Rhode Island’s casinos, where state law allows separately enclosed sections, showed that the level of pollution increased even more as smoking was concentrated into smaller areas. (See chart to the left.). Smoking rooms mean workers in the building are still exposed to toxic air. (See chart below)16

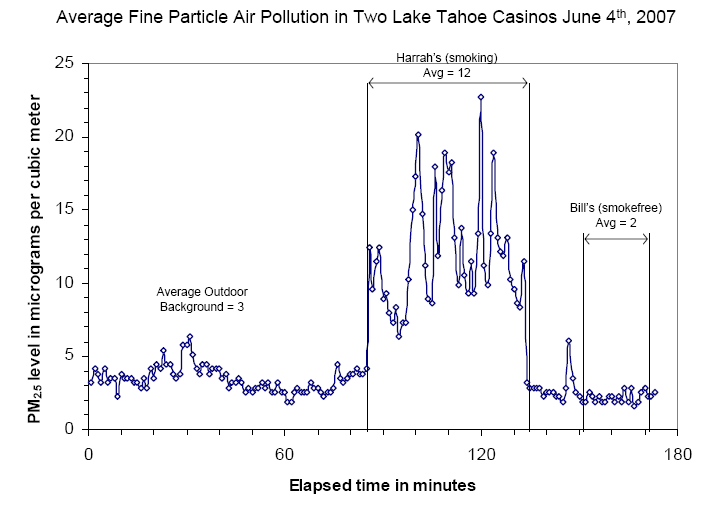

- Fine particle air pollution was measured in two Nevada casinos: one smokefree casino and one smoke-filled. The smokefree casino had good air quality indistinguishable from outdoor air levels. The smoke-filled casinos had air particle pollution levels 5 to 18 times higher than the smokefree casino. (See chart below)17

SMOKEFREE GAMING: YOUR SAFEST BET.

- The National Council of Legislators from Gaming States (NCLGS) approved a landmark resolution in January 2009 encouraging state lawmakers to ensure that casinos are smokefree workplaces.18

- Smokefree laws have no effect on total gambling revenues or on the average revenue per machine. Despite smokefree opponents’ claims of economic doomsday, smokefree laws do not harm casinos or other gambling venues, just as they do not harm restaurants, bars, or bingo parlors. Smoking is an incidental activity.19

- The Washington State Department of Revenue issued an economic report in June 2008, which found that gaming revenues have increased in commercial casinos since the statewide smokefree law took effect. The repost cites the biggest turnaround as being gambling businesses, whose gross income increased 7.2 percent in 2007 after losing 9.8 percent in 2006. The industry had been in decline before the law took effect, dropping 5 percent in 2005 and 8.6 percent in 2004 after a 19.5 percent gain in 2003.20

- The Massachusetts Smoke-Free Workplace Law has not adversely affected keno sales since it went into effect on July 5, 2004. Net keno sales have increased approximately $121,000 per year since 2000. The number of dollars waged per month also remains unchanged. Since the 100% smokefree law was implemented, there has been no significant change in this trend.21

- Smokefree laws do not adversely affect charitable bingo profits. A 2003 study analyzing 16 years of charitable bingo economic trends in Massachusetts before and after local communities adopted smokefree ordinances found that charitable bingo profits began declining before Massachusetts’ communities starting going smokefree and that there was no effect on bingo revenues within the population covered by smokefree policies.22

- According to the California Board of Equalization, California’s bars, casinos and gambling clubs continue to profit since going smokefree in January 1998. Sales tax receipts show that revenues in establishments licensed to serve alcohol – including casinos and gambling clubs that serve alcohol – increased by more than 5 percent each quarter of 1998 over revenues each quarter in 1997.23 In these same establishments, sales increased from $8.64 billion in 1997 to $11.3 billion in 2002.24

PATRONS & THE PUBLIC SUPPORT SMOKEFREE GAMING

- A 2005 study measuring the smoking rates of gamblers in Las Vegas, Reno, and Lake Tahoe found no statistically significant difference from the national smoking prevalence of 20.9% Smoking prevalence in Las Vegas, Reno/Sparks, and Lake Tahoe casinos, was respectively 21.5%, 22.6%, and 17%.25 Casino claims that gamblers smoke more are false.

- More than 70% of New Jersey voters support extending the statewide Smoke-Free Air Act to cover casino gaming floors. This support comes from voters across the state, including 72 percent of Democrats, 68 percent of Independents, and 63 percent of Republicans.26

- The J.D. Power and Associates 2008 Southern California Indian Gaming Casino Satisfaction Survey found that 85% of gaming customers at Indian casinos in Southern California would prefer a smokefree environment in these casinos.27 Another survey found that 91% of Californians would be more likely to visit tribal casinos or would not change patronage if casinos went smokefree.28

- 70% of polled poker players agree that all poker tournaments should be smokefree.29

- 73% of Illinois voters support Illinois’s smokefree law that includes all casinos, racetracks, and other gaming facilities.30

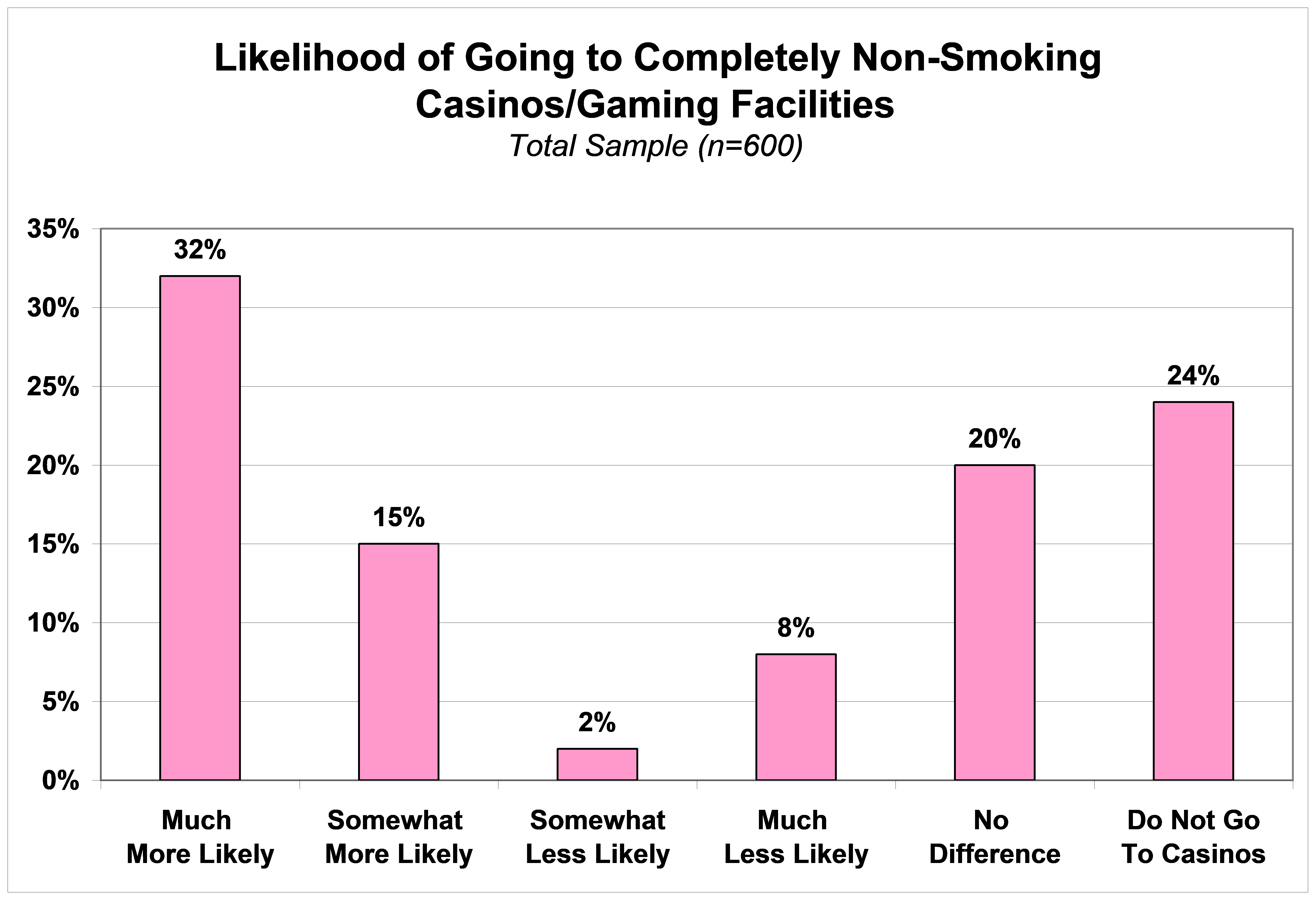

- A 2007 New Mexico survey found that 67% of residents prefer smokefree gaming venues including persons living in the area of the Navajo Nation. 47% said they would be more likely to patronize a casino if it were 100% smokefree. (See chart to below)31

- 78% of Delaware voters felt the right of customers and employees “to breathe clean air inside public places, like restaurants, bars, and casinos” were more important than the desire of smokers to smoke inside public places. Respondents believed that Delaware’s restaurants, bars, and casinos are healthier and more enjoyable now that they are smokefree: 90% responded that smokefree environments are “healthier for customers and employees”, and 83% believed going out to be more enjoyable and pleasurable.32

- In Maine, 77% of residents surveyed agreed that “all Maine workers should be protected from exposure to secondhand smoke in the workplace.” Over time, that number went up 11 points to 88%. Not only did former smokers (77%) express support for a smokefree gaming law, but also over half of current smokers polled (54%) said they support Maine’s bingo law.33

- In Montana, 66% of Helena residents surveyed “support” an ordinance that makes all indoor air places smokefree, including casinos; 54% of whom “strongly support” such an ordinance. In 2002, Helena voters passed a comprehensive smokefree law, but six months after enactment, it was challenged in court and enforcement of the law ceased.34

May be reprinted with appropriate credit to the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation.

Copyright 2009 American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. All rights reserved.

REFERENCES

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006.

- National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety. Environmental and Biological Assessment of Environmental Tobacco Smoke Among Casino Dealers, May 2009. Download at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2005-0201-3080.pdf

- Curran, J., “For casino workers, smoke study underscores hazard,” Newsday/AP, October 17, 2004.

- Repace, J., “Secondhand Smoke in Pennsylvania Casinos: A Study of Nonsmokers’ Exposure, Dose, and Risk,” American Journal of Public Health published online ahead of print June 18, 2009.

- Trout D.; Decker J.; Mueller C.; Bernert J.T.; Pirkle J., “Exposure of casino employees to environmental tobacco smoke,” JOEM. 1998 March;40(3): 270-6. Accessed on May 20, 2004. Download at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9531098?dopt=Abstract.

- Anderson, K.; Kliris, J.; Murphy, L.; Carmella, S.; Han, S.; Link, C.; Bliss, R.; Puumala, S.; Hecht, S., “Metabolites of Tobacco-Specific Lung Carcinogen in Nonsmoking Casino Patrons,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 12:1544-1546, December 2003.

- Repace, J., “Respirable Particles and Carcinogens in the Air of Delaware Hospitality Venues Before and After a Smoking Ban.” JOEM, September 10, 2004.

- Collier, A.C., Dandge, S.D., Woodrow, J.E., Pritsos, C.A.; “Differences in DNA-damage in non-smoking men and women exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS)” Toxicology Letters 158(1): 10-19, July 28, 2005.

- Pilkington, et. al., “Health impacts of exposure to second hand smoke (SHS) amongst a highly exposed workforce: survey of London casino workers,” BMC Public Health 2007, 7:257. Download at: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-7-257

- Geoffrey T. Fong, et. al., “The Impact of the Smoke-Free Ontario Act on Air Quality and Biomarkers of Exposure in Casinos: A Quasi-Experimental Study,” Ontario Tobacco Control Conference, Niagara Falls, Ontario, December 2, 2006.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006.

- Samet, J.; Bohanon, Jr., H.R.; Coultas, D.B.; Houston, T.P.; Persily, A.K.; Schoen, L.J.; Spengler, J.; Callaway, C.A., “ASHRAE position document on environmental tobacco smoke,” American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), October 22, 2010. Download at https://no-smoke.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/ASHRAE_PD_Environmental_Tobacco_Smoke_2019.pdf.

- [n.a.], “Casino Queen Before and After Smokefree Law PPT slide,” Roswell Park Cancer Institute, [n.d.].

- [n.a.], “Colorado Casinos Safer After Smoke-Free Law: Research Shows Air Quality Improvement in Casinos’ First Smoke-Free Month,” California Department of Public Health, February 26, 2008.

- Repace, J., “Respirable particles and carcinogens in the air of Delaware hospitality venues before and after a smoking ban,” Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 46(9): 887-905, September 2004.

- New Jersey GASP, “[press release re: Indoor air quality testing in Rhode Island and New Jersey casinos.],” New Jersey GASP, February 5, 2007. Download at: https://no-smoke.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/ac_pressrelease.pdf

- Travers, M., “[Presentation at Fallen Leaf Lake 2007.],” Roswell Park Cancer Institute, June 2, 2007.

- Adopted by the NCLGS Executive Committee on January 10, 2009. Accessed on June 23, 2009 at http://www.nclgs.org/PDFs/8000827h.pdf

- Mandel, L.L.; Alamar, B.C.; Glantz, S.A., “Smoke-free law did not affect revenue from gaming in Delaware,” Tobacco Control; 14: 10-12, 2005.

- Gowrylow, M. “press release: Businesses bounce back from smoking ban,” Washington Department of Revenue, June 10, 2008.

- Connolly, G.N.; Carpenter, C.; Alpert, H.R.; Skeer, M.; Travers, M., “Evaluation of the Massachusetts Smoke-Free Workplace Law: a preliminary report,” Division of Public Health Practice, Harvard School of Public Health, Tobacco Research Program, April 4, 2005.

- Glantz, S.A.; Wilson-Loots, R., “No association of smoke-free ordinances with profits from bingo and charitable games in Massachusetts,” Tobacco Control;12: 411-413, 2003.

- [n.a.], “Smoke-Free Bar Fact Sheet,” BREATH, [n.d.].

- California State Board of Equalization: California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section, November 2002; State of California, Employment Development Department, Labor Force Statistics, November 2003.

- Pritsos, C.A., “The percentage of gamblers who smoke: a study of Nevada casinos and other gaming venues,” Reno, NV: University of Nevada, Department of Nutrition, 2006.

- [n.a.], “[press release re: ‘New poll finds nearly 7 in ten New Jersey Voters Support Smoke-Free Casinos,’” NJ Breathes, October 31, 2007.

- J.D. Power and Associates Reports: A Vast Majority of Southern California Indian Gaming Casino Customers Express Desire for a Smoke-Free Environment, July 1, 2008.

- Field Research Corporation, “2004 Field Research Poll Results,” California Department of Health Services, September 2004.

- Dalla, N., “Poll Results: To Smoke or Not to Smoke – That is the Question,” Card Player, December 17, 2003.

- [n.a.], “Commercial tobacco-free Illinois Frequency Questionnaire,” Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, June 1, 2008.

- [n.a.], “New Mexicans Concerned About Tobacco (NMCAT) Tobacco Policy Survey December 2007, “ Research & Polling Inc., December 2007.

- [n.a.], “Delaware Statewide Survey,” IMPACT, American Lung Association, American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, [n.d.].

- [n.a.], “A Snapshot of Perspectives on Second-Hand Smoke in the Workplace,” Critical Insights, September 2004.

- [n.a.], “[Press release re: “Helena Voters Overwhelmingly Support the City’s Smoking Ordinance, and Believe it Should Be Fully Enforced Without Delay.”],” Harstad Strategic Research, Inc., June 27, 2004.