The availability of smokefree multiunit housing continues to increase around the United States. Despite the progress, additional action is needed on this important public health issue. Nonsmokers who live in multi-unit residential buildings, such as apartments and condominiums, can be exposed to secondhand smoke that drifts into their unit from elsewhere in or around the building.1

Research demonstrates that secondhand smoke can travel throughout buildings through doorways, halls, and windows, as well as through the ventilation system, electrical outlets, and gaps around doors, fixtures, and pipes.2, 3

The U.S. Surgeon General confirmed that there is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke and that even low levels of exposure, and occasional exposure, can be harmful to health. The only way to protect health is for buildings to be completely smokefree.4, 5

Many people remain exposed to secondhand smoke in multiunit housing. A 2015 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that more than 1 in 3 nonsmokers who live in rental housing are exposed to secondhand smoke, as are 2 in 5 children—including 7 in 10 African-American children, which underscores the need for expanding the availability of smokefree housing.

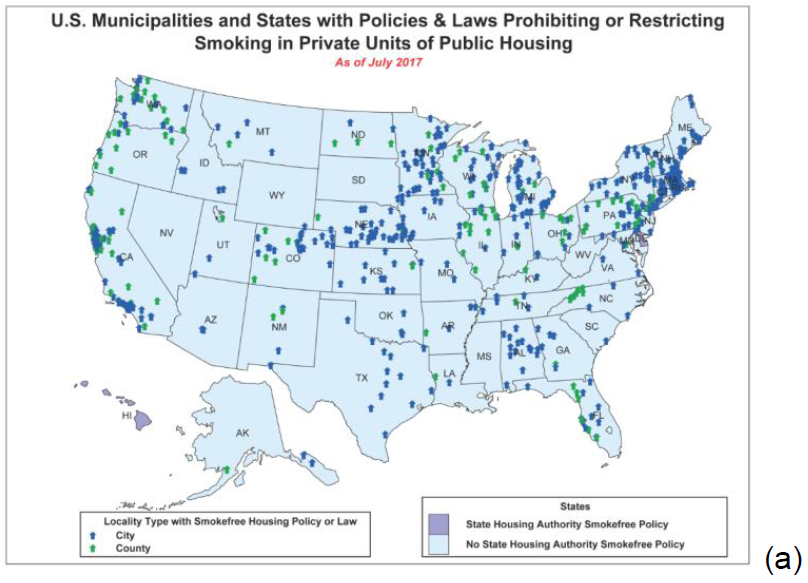

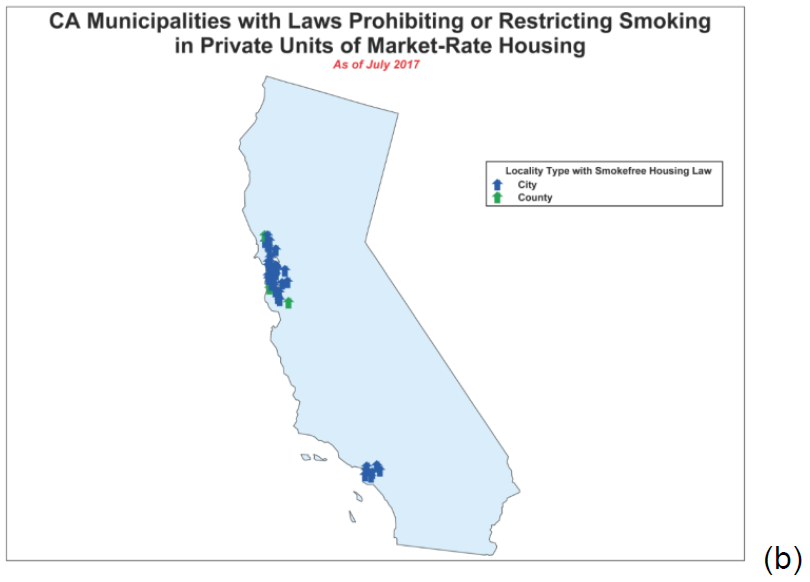

Note: Communities with only indoor common area smoking restrictions or other restrictions that do not address smoking in units are not represented on these maps.

Note: This document was written in 2017. For updated numbers and more information, please take a look at our most recent U.S. Laws for 100% Smokefree Multi-Unit Housing and/or U.S. Public Housing Authority Policies Restricting or Prohibiting Smoking lists.)

Map (a): Municipalities & states with a policy or law that fully or partially prohibits smoking in private units of public housing.

- As of July 1, 2017: at least 585 municipalities have a policy and/or law that partially restricts or fully prohibits smoking in private units of multi-unit public housing buildings. In these municipalities, 432 policies prohibit smoking in 100% of units and 155 policies restrict smoking in only some units.

- There are a total of 587 municipal laws/policies, which represent 527 policies adopted by local Public Housing Authorities and 60 laws enacted by local ordinance.

- ANR Foundation knows that more than 600 Public Housing Authorities have adopted smokefree policies, and is in the process of obtaining copies of policies and other documentation in order to analyze and add the policies to the U.S. Tobacco Control Laws Database©.

- Smoking is prohibited in all units of all buildings under the jurisdiction of the Delaware State Housing Authority and the Hawaii Public Housing Authority.

- Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Washington prohibit smoking in all units of all buildings financed through the states’ housing finance agencies.

In November 2016, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issued a smokefree public housing rule which requires Public Housing Agencies/Authorities to adopt and implement smokefree policies for all of their public housing properties by August 2018. HUD’s decision will help ensure that the 2 million people living in public housing have the ability to breathe smokefree air at home.

Map (b): Municipalities with laws that partially or fully prohibit smoking in private units of multi-unit housing.

- All adopted by ordinance at the city or county level. Most of these laws apply the same smoking restrictions to all specified multi-unit buildings, including market-rate and public housing.

- As of July 1, 2017: 60 municipalities have laws that partially restrict or fully prohibit smoking in private units of multi-unit housing throughout the community.

- Of these, 32 municipalities have laws in effect that prohibit smoking in 100% of private units of all specified multi-unit housing throughout the community. Smoking is also prohibited on patios, balconies, or other outdoor private use areas.

- An additional 8 municipalities have enacted laws that will prohibit smoking in 100% of all specified multi-unit housing throughout the community, but they are not yet in effect.

- An additional 20 municipalities have laws in effect that restrict smoking in private units of specified multi-unit housing, but do not currently require all units or all buildings to be smokefree.

- These laws contain a wide variation of restrictions on smoking in private units, such as: applying only to new buildings but not to existing buildings or designating a certain percentage of private units as nonsmoking or limiting smoking to certain buildings or permitting current residents to continue to smoke indefinitely.

In addition to the approaches represented by Map (a) and Map (b), other approaches are being taken to increase the availability of smokefree multi-unit housing.

The most widespread is the “voluntary approach,” which means that a housing provider chooses to adopt a smokefree policy for the building(s) that they own or manage. Many communities are working with market rate and affordable housing providers to educate them about why and how their buildings can become smokefree, and to help them adopt and implement a no-smoking policy. Benefits of the “voluntary approach” include that a policy can be adopted by almost any owner in any community, and can be implemented in a relatively short amount of time in order to have a quick impact on the health of the building’s residents. The voluntary approach means that making progress in a community can be gradual since a coalition is working with each building’s owner or management company to adopt an individual policy. The voluntary policy approach may also mean that a policy could be repealed or not applied or enforced equally across units, especially if there is a change in management.

Another approach is for Housing Finance Commissions and other affordable housing funders to stimulate smokefree affordable housing by either incentivizing or requiring the adoption of a smokefree policy for properties whose developers receive funding through their Low Income Housing Tax Credit programs. There are 5 states and at least 8 municipalities that have created an optional tax credit for having a smokefree policy for the building, with the intention that property developers who select this financial incentive will help increase the availability of smokefree affordable buildings. Another six states—Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Washington—now require, rather than encourage, all buildings to be smokefree that are financed through their housing finance agency’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit program.

Disclosure laws are yet another approach that communities and states are taking to support smokefree housing. Disclosure laws do not require buildings to be smokefree, but rather these laws aim to encourage the growth of smokefree buildings by requiring housing providers to monitor and disclose the status of smoking and non-smoking units in their building(s) to prospective residents. Some disclosure laws have additional requirements, such as notifying prospective residents how complaints about drifting smoke are addressed. Maine and Oregon, plus at least 30 municipalities, have adopted disclosure laws. The intent of disclosure laws is to give people a tool to make a more informed decision when looking for housing, and help increase public demand for the availability of smokefree multi-unit housing.

Visit ANRF’s smokefree multi-unit housing page at no-smoke.org/at-risk-places/homes/ for more information.

May be reprinted with appropriate credit to the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation.

Copyright 2017 American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. All rights reserved.

REFERENCES

- King, B.A.; Peck, R.M.; Babb, S.D., “National and state cost savings associated with prohibiting smoking in subsidized and public housing in the United States,” Preventing Chronic Disease 11(E171), October 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2014/pdf/14_0222.pdf

- King, B.A.; Travers, M.J.; Cummings, K.M.; Mahoney, M.C.; Hyland, A.J., “Secondhand smoke transfer in multiunit housing,” Nicotine and Tobacco Research, October 1, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20889473

- Repace, J. “Smoke Infiltration in Apartments.” 2011. http://www.repace.com/pdf/REPACE_Recent%20Advances_ISES%202011.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/secondhandsmoke/fullreport.pdf

- “How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/.